Hello all,

Today I would like to talk about the folk costume and embroidery of the Biłgoraj / Bilhoray, and Sieniawa / Senyava regions. This is claimed by both the Polish and the Ukrainians, and it seems that both lived in this region. This area was part of 'Red Rusynia', the zone between the Sian / San and Boh / Bog rivers, which was at various times part of the Kievan empire or of the Kingdom of Poland, or under the control of various local aristocrats. The population was largely Ukrainian, but Polish settlers came over the centuries, and some of the population was Polonized. This area was at the very edge of Ukrainian settlement, and the western parts were likely natively Polish.

Here is a map of the ethnic makeup of Kholm / Chelm province in 1875. You can see that the region of Bilgoraj / Bilhoray lies right at the edge of Polish and Ukrainian ethnographic zones.

Here is a closeup of Kholm / Chelm Province in 1913. You can see that the Bilgoraj /Bilhoray region is at the extreme southwest edge.

The southern border of this area is that between the Muscovite Empire and the Austrian Empire, so that part of this cultural area actually fell on the Austrian side. [Remember that neither the Polish nor the Ukrainians had a State at this time, both being divided by various Empires.]

When the Polish State was reinstated after WWI, this area, along with much of Western Ukraine, was included. When the borders were redrawn after WWII, the area once known as Red Rusynia was mostly included within the borders of Poland. There was an 'exchange of populations', with people being deported in both directions. Today this area is overwhelmingly Polish, with small Ukrainian populations remaining.

This costume is considered to be extremely archaic, with many ancient Slavic characteristics.

In many details it resembles Ukrainian costumes, but it also closely resembles that of the purely Polish Lasowiacy, who live just west of the Sian near Tarnobrzeg. For comparison, here are a couple images of the Lasowiacy costume.

This woman is from the village of Grębów in the Lasowiacy region, but one will sometimes see her photos labelled as being from the Bilgoraj. region. Note especially the different headpiece.

These two maps show the Bilgoraj cultural region as currently defined by Polish Ethnographers.

This costume region actually extends further south, but the villages in the south were mostly Ukrainian majority. There is evidence of at least the Ukrainian village of Dobra using this same costume. Others to the east are described as using basically the same costume but with cross stitch embroidery.

The basic garment is, as usual the chemise, here called koshula. Both men and women wore the shirt with shoulder inset, or ustawka cut. For the men it reached the knees, for the women they were longer.

Women's dress chemises had embroidery on the cuff, collar, and shoulder inset. Occasionally on the front placket, by the opening. The shoulder inset was embroidered on three sides, next to the seam, and also had a line of embroidery up the middle. The lines that frame the inset were, at least originally, decorative joining stitch that actually formed the seams. There was also a band of embroidery on the upper sleeve and the front and back fields next to the inset. This could be quite simple or rather elaborate.

The collars of the shirts are secured with studs called spinka. These are threaded through two buttonholes, like cufflinks. Alternatively, they were tied closed with a ribbon, often red.

The skirt, in this region called fartukh, was of a few types. The oldest was of plain white linen, gathered into a waistband. For everyday of coarse, unbleached linen, and for dress at least four widths of fine, highly bleached linen.

Later, the skirts were made of hand printed fabric. The women would spin and weave the cloth, and bring it to artisans to have it block printed. These people would have carved wooden blocks with various designs available. Here is a closeup of such fabric, one of the blocks used to print such designs, and a skirt of printed cloth. Such a skirt was called Malovianka. They were very widespread in parts of eastern Poland and western Ukraine.

Here is a woman from the village of Dobra wearing such a skirt.

In winter, a skirt of linsey-woolsey was worn. These were woven with a linen warp and a woolen weft. The weft was woven of narrow alternating black and white stripes.

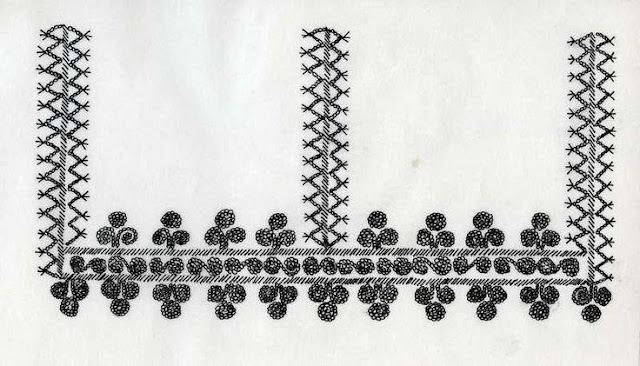

The apron, called zapaska, was made of two fields with a decorative joining stitch holding them together. There was also embroidery on either side of the joining stitch, and also along and near the hem.

Later the aprons were made of one field of linen, as wider cloth became available, However the central vertical band of embroidery remained.

Skirts and aprons were sometimes secured with inkle woven sashes. These were necessarily worn over overcoats to hold them in place, but were at times also worn over the shirt, skirt, and apron.

Many people went barefoot in the summer, but when footwear was needed, then linen or woolen cloths were wrapped around the feet, and leather moccasins, khodaky, were worn.

Necklaces were, of course, part of the dress outfit. Amber, strings of beads, balamuty, coral, and coins known as dukaty were worn. Nothing distinctive to the region, these were all widespread.

Roman Catholics sometimes wore scapulars, either bought, often on a pilgrimage,

or homemade.

Single girls wore their hair uncovered, usually in braids. When they wished to dress up, they would braid wreaths out of flowers, or just put ribbons and/or flowers in their hair.

Married women, of course, kept their hair covered, as was the custom in Europe. A wooden ring covered in cloth about 15 cm in diameter, khamelka, was placed on the top/back of the head.

The hair was pulled back and wrapped around this ring, holding it in place. The loose ends were left on the inside of the ring. Over this a cap, chepets, was placed, The back of the cap was often of sprang, the drawstring was pulled tight, and the ribbons tied in back. On special occasions a band of embroidered cloth sewn into a ring, called zatychka, was placed around the chepets, which fitted tightly on the outside.

When the new style chepets was used, sometimes the zatychka was also of bought cloth.

For exceptionally important occasions, a long rectangular piece of linen, in many places called rantuch, but here just called nadkrywka was placed over the head and shoulders.

The embroidery in this region, while resembling other styles present in eastern Poland and western Ukraine, is rather unique. The embroidery is executed on the shirt: collar, cuffs, shoulder insets, and sometimes front, the apron, the zatychka which is wrapped around the cap, the nadkrywka, the apron, and sometimes the skirt. The embroidery is done in red or black, occasionally both.

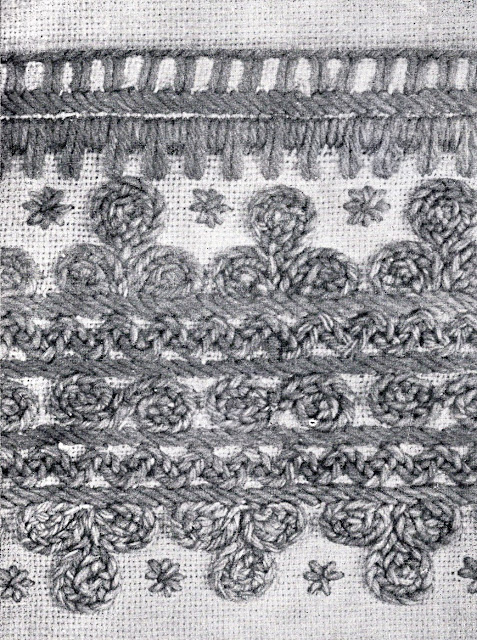

The stitches used are mostly counted satin stitch, laid parallel in short stitches to form lines, or at angles to form triangles or stars.

Curvilinear designs are also used, laid in spirals and groups of spirals, in 2s, 3s, or 5s.

The spirals and other motifs may be executed in chain stitch. Here are some examples from the village of Naklik. These embroideries are from zatychky.

This embroidery is from a zatychka from the village of Przysiadki. [Google has no record of such a village, but I have found hints that it was not far from Lipiny or Potok Gorny]

Other examples:

In other places the spirals and curvilinear motifs were executed in stem stitch.

Here is an example from the village of Dobra. Here we can see the seams in relation to the embroidery. Note that this particular shirt has a stand up collar.

This zatychka is from the village of Maijdan Sieniawski.

Note that this cuff is gathered differently than the ones shown above.

In recent years performing groups have decided not to bother with the authentic married woman's headpiece. Instead they took the zatychka and sewed a circle of cloth to the top to make a cap. THIS IS NOT AUTHENTIC.

For the most part, they have also done away with the wooden hoop that holds its shape, so that it is soft and floppy. They also sit on the head in the wrong way, being pinned to the top of the head. Compare the authentic headpiece;

They sit on the head incorrectly, they are sometimes soft and flimsy, and they are often too big.

The first couple girls, i suspect are not even married.

The better examples of this have the women put their hair up, at least.

You will see examples where this detail is ignored.

This woman's hair, is, perhaps, too short to put up.

But this following example is inexcusable. Here they have plopped the cap on top of modern hair styles hanging out.

THIS SHOULD NEVER BE DONE.

This example is actually not bad. The fake chepets is placed correctly, although they have replaced the ribbons that hold the chepets with a fake bow in linen. [And, she has the shirt on backwards...]

I will have to end here and make a second part to this article. Here are just a few more images of this outfit, both authentic and stage versions.

Thank you for reading, I hope that you have found this to be interesting and informative.

Roman K

email: rkozakand@aol.com

Source Material:

Barbara Kaznowska-Jarecka, 'Stroj Bilgorajsko-Tarnogrodzki, APSL vol 20', Wroclaw, 1958

Petro Odarchenko et al, 'Ukrainian Folk Costume' Toronto, 1992

Kazimierz Pietkiewicz, 'Haft i Zdobienie Stroju Ludowegu', Warsaw, 1955

Aleksander Blachowski, 'Hafty Polskie Szycie', Lublin, 2004

Olena Kul'chyts'ka, 'Narodnyj Odiah Zakhidnykh Oblastej Ukrajiny', L'viw, 2018

Stanislaw Gadomski, 'Stroj Ludowe w Polsce', Warsaw, 1985?

Aleksander Jackowski, 'Sztuka Ludu Polskiego', Warsaw, 1967

Valentyna Borysenko et al, 'Kholmshchyna i Pidliashshia', Kyiv, 1997

Elzbieta Piskorz-Banekova, 'Polskie Stroje Ludowe, vol 1', Warsaw, 2013

Jadwiga Turska, 'Hafty', Warsaw, 1970

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20-%20Copy.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20-%20Copy.jpg)

%20(3).jpg)

Thanks for this very comprehensive writeup!

ReplyDeleteI'm wondering if you have anything on the Przemyśl-Jarosław costume.

I've seen some people on Polish folk costume groups say that the village of Dobra belongs to this costume group.

All I've been able to find, in addition to your post on the costume of Torki and Sośnica, was this scan from Biuletyn Informacyjny Polskiego Towarzystwa Ludoznawczego:

https://www.instagram.com/p/CNhktxeri4J

This photoshoot by the Union of Ukrainians in Poland, which included costumes from the area of Przemyśl, some of which look quite similar to the picture of the girl in the above bulletin: https://ukraincy.org.pl/perly-pogranicza/

And the aprons on page 141 and 142 and possibly also the married woman's cap with the 'zawicie' on page 81 of this publication:

http://muzeum.przeworsk.pl/wp-content/uploads//2017/10/Ludowe-stroje-przeworskie_net.pdf

I'm extremely curious about this costume because it seems to be incredibly colorful and unusual embroidery.

Unfortunately it seems to me that Polish ethnographers had very little interest in Ukrainian, Belarusian and Ruthenian

costume (with the notable exception of Hutsul costume) and as a result most of it remains undescribed.

I'm a bit confused by what you mean when you say preforming groups. Are these members of the ethic group who also preform? Are they unrelated people? If the former, I fail to see how you have any business telling how or how not to wear their clothing. Perhaps what you mean to say is 'this is not the traditional way' otherwise I really appreciate your work and have very much enjoyed reading it all! Thank you!

ReplyDelete