Hello all, Today I will talk about how the Filipino National costume developed further in the late 1800's and early 1900's. The national costume became the major dress of the Christianized lowland populations of the Philippines, regardless of ethnic group or language, encompassing the Tagalog, Ilicarno, Visaya, Cebuano, etc. It was especially connected to the growing mestizo population of the Philippines, who were ethnically mixed, whose native ancestry was combined with the blood of Spanish, Chinese, Mexican and other migrant groups. Wealthy and upper class people, native and mestizo began to look down on purely native forms of clothing and aspired to a 'higher' expression of dress. Thus a new form of attire, the 'Maria Clara dress', also called 'Traje de Mestiza' or Filpiniana, was born. I feel that I have to point out that while this attire was strongly influenced by European culture and ideals, it was in fact a completely Native Filipino development. Spanish colonials in the Philippines did not wear this.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maria_Clara_gown

First of all, the components of the attire were renamed. The alampay became the pañuelo, the baro became the camisa, and the tapis became the dalantal or sobrefalda. The saya, being of Spanish origin retained its name.

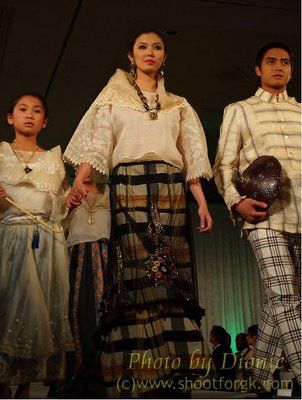

The upper garments of both men and women in this time were no longer woven with colored stripes, but became completely made up of gauzy cloth of a single, usually pale color, with either woven in or embroidered ornament. Wealthy Mestizas lowered the neckline of the camisa, and the sleeves became very wide ['butterfly' or 'pagoda' sleeves]. The body remained fairly short, and hung just to the waist outside the lower body clothing, as befits a hot climate.

You can see this last one has a modesty panel sewn to the inside. This is an early 20th cent. example, and the body has been shaped for a more tailored fit.

The pañuelo, which originally had been worn over one shoulder, used as a sweat cloth or thrown casually over the head, now became ensconced as a fichu, folded in half diagonally, then folded a couple more times and wrapped around both shoulders, the ends being fastened in front. This echoed the European fashion of the time, and mitigated the sheerness of the camisa, offering some modesty. It also provided a place to pin jewelry.

The saya became fuller, being made of up to 7 gores 'siete cuchillos' sewn together, each one tapering towards the waist and becoming wider at the hem. These panels could be single or double. They reached the floor; skirts for wealthier women, or for more splendid occasions developed trains that trailed behind them. They were no longer sewn of plaid material, that was too déclassé and 'native'. They were made of single colored or striped thin silk, abacá, piña, or other cloth. Petticoats were introduced to enhance the fullness of the saya.

The tapis, dalantal or sobrefalda became reduced in size as it no longer served as the main lower body covering. It was no longer woven with stripes in the native style, because anything 'native' was looked down upon. As the skirt became fuller it became impossible to wrap the tapis all the way around and tuck it in, so it developed two cords at the upper corners which tied around the waist. It became an accessory, often being made of sheer, mesh, or highly ornamented cloth. It was sometimes made of gauzy embroidered piña cloth. It also began to be wrapped front to back, like an apron, rather than back to front, as was originally the case. Peruse the various images above.

As is often the case, the sensibilities of the upper classes affected the dress of lower class Filipinas, who followed suit as best they could, although they could not afford the expensive materials of the wealthy, and eschewed the more impractical elements, like the train, as they actually had to work. We see here several examples of mixtures of older and newer elements.

This last image hints at the 20th cent innovation, often called Terno, although many continue to call it the Filipiniana or Maria Clara gown. In this version, the cap of the sleeve is extended in an upward direction, and the pañuelo is dispensed with. The camisa and saya are made of the same material, or sewn as one piece like a modern gown. Many different cuts were invented by Filipino designers, and these sleeves became the distinctive Filipino characteristic. Here we see Imelda Marcos wearing one such gown.

Some other examples of the great variety of the terno in the 20th cent. Filipino designers continue to elaborate on the theme even today.

I will close with some more images of this costume in various stages of development.

I

Thank you for reading, I hope that you will find this to be interesting and informative.

Roman K.

email: rkozakand@aol.com

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_MET_115249a.jpg)

.jpg)